Study after study has revealed a disparity between how men and women use and experience public transport. From questions of safety to the types of trips undertaken and reasons for travel, there is a clear gender divide when it comes to transport.

To better understand this gender mobility gap, researchers set out across three African cities to gather both quantitative and qualitative data that might explain the barriers women face when using public transport. Only through a mix of such data can a clearer picture be developed of how exactly the systems that work for one gender can prove a hindrance to another.

Gender just one aspect influencing transport experience

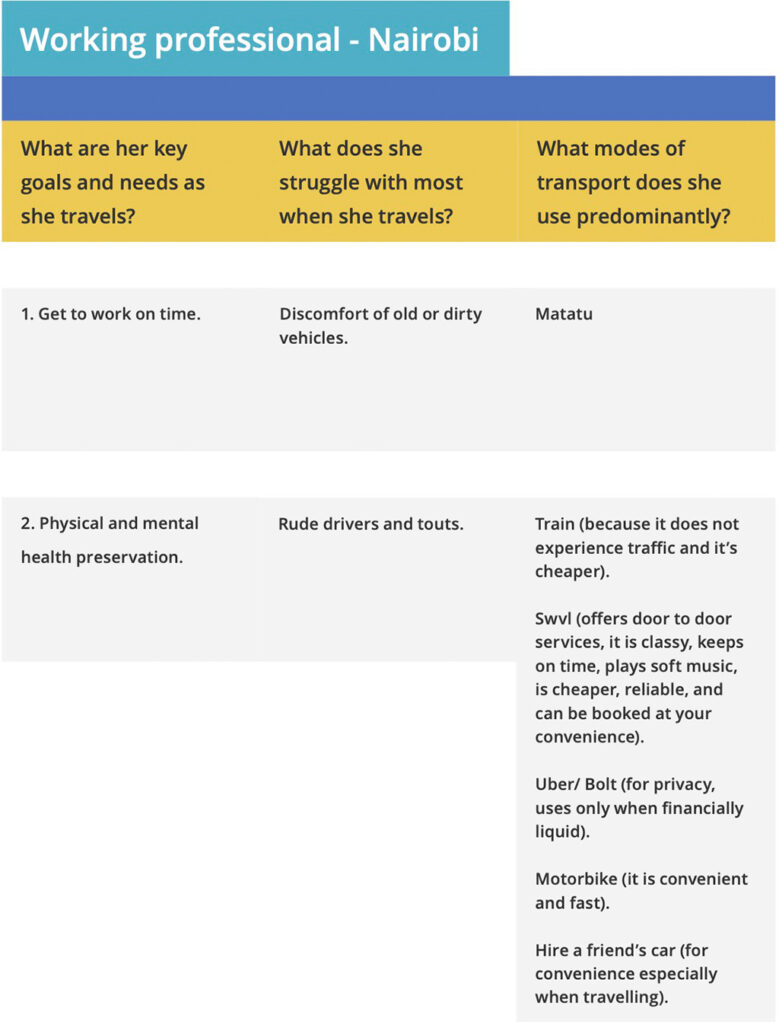

Decoding women’s transport experiences: A study of Nairobi, Lagos, and Gauteng from WhereIsMyTransport compiles the results of this five-month research project aimed at illuminating which obstacles women faced through a more nuanced lens. While past studies have often relied solely on surveys which focused on gender disaggregation, researchers took a broader, gender-sensitive approach to data collection that allowed researchers to zoom in on other aspects that might impact women’s public transportation experiences. After all, gender is only one demographic factor driving women’s choices. Other aspects of their lives, such as their ages, their professional distinctions (i.e., students, stay-at-home mothers, and sexworkers), and their socio-economic classes may play a decisive role in their choices.

“Our aim with this study was to move the conversation away from women as a homogenous group,” the report clarifies. Using a methodology that combined digital and in-person questionnaires with in-person group workshops and ride-alongs to observe different individuals during their daily commutes, researchers were able to ascertain not only what obstacles existed but also how these hinder or impact individual travel choices.

Through this anonymized qualitative data, researchers could show both commonalities as well as identify areas where differentiation was key. Among the similarities revealed across age groups and geography, for example, was the frequent comment that the stress of using public transport brought women fatigue. At the same time, a student who shared her travel experiences in Nairobi portrayed a vastly different decision-making matrix than a working mother in Gauteng. Though they both noted concerns about safety and sexual harassment as well as affordability, the former prioritized low costs whereas the latter chose to use an Uber to get to her destination more quickly.

This variance in commuting patterns can prove useful to those who are in search of potential solutions to women’s concerns. As the report says, the depth of this data is more comprehensive than quantitative data alone. “From an urban or transport planning perspective, the kind of data collected for this study should be a prerequisite for any Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan or National Urban Mobility Plan.” To that end, these more individualized approaches to data collection provided researchers with interesting insights in each of the three cities.